The sedum bloomed a field of brilliant yellow flowers, the sempervivum spawned families of hens and chicks. The wild strawberries had no runners but took up the slack, promiscuously seeding about. Willful explorers from my potted garden defiantly rooted into crushed slag on the top of an apartment building, twenty-one stories above city sidewalks and when green roofs were not yet a thing. It was also before I joined the Manhattan Chapter of NARGS, but suddenly rock gardening looked like a game-changer.

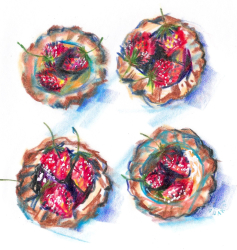

That was over forty years ago and, incidentally, my first and last attempt at farming. I would sell teacup harvests of intensely flavored fraises des bois (Fragaria vesca), the size of a pinky nail, to a four-star French restaurant down the block. The pastry chef at Daniel used my mini-crops sparingly, like jewels, to decorate after-dinner tartlets.

Rockeries often are the jewels in a garden, creating dazzling brilliance where it is least anticipated. Or most needed. Especially to those of us who might have thought that NARGS is ignoring anyone with merely a fire escape on which to garden.

Yet what defines a rock garden? Can a rockery be planted in nothing more than a sidewalk street-tree pit? In rubble from an excavation site? Or on an aluminum ledge intended to cap off and protect a parapet wall but which had become a setting for abandoned equipment boxes, pigeon poop, and dangling cables, not to mention the ongoing drone of air conditioners? No realtor wanted to show me such an eyesore, afraid it would put the kibosh on any potential deal. Little did they suspect that problem-solving is one of the reasons why I garden.

Nevertheless, here was your typical urban rooftop. I know because I saw a city full of them when I was looking to move, but none that I could afford unless I forfeited outdoor space. Extra closets or a second bathroom (perhaps for the kitties’ litter boxes, as civilized as that would have been) meant nothing. Outdoor space was non-negotiable if I was going to spend the rest of my days in this city. I was seeking a forgotten bit of underutilized real estate, plus the privilege of gardening at the top of quirky early twentieth-century architecture. I did not care if the garden circumnavigated an apartment that was no bigger than an afterthought. Besides, I had looked long enough and the light was dreamy on that Friday, July 13th.

“I will work with this” became my mantra.

The Ledge started as nothing more than a holding area, an outdoor waiting room for a growing collection of pots. Yet self-driven schemes can be fueled with a unique spirit lacking in AutoCAD designs. Moreover, as any container gardener knows, one vessel leads to another when everything is repurposed by drilling a drainage hole. I will work with what I find, anything that strikes my idiosyncratic aesthetic.

From the end of May through early August, The Ledge gets sunshine for hours. During the winter months the light quickly falls behind surrounding architecture or never clears it at all. After years of plant sale temptations, I am still discovering which shallow-rooted alpines are at home on an unforgiving urban rooftop that is wildly windy in the winter and hot enough to fry an egg in the summer. Yes, I might have been up for the challenge, but I never would have thought that a subversive gathering of mats, cushions, and buns on an aluminum ledge could morph into one of the most engaging gardens that I ever planted.

Yet my failures are memorable and discouraging. The saxifraga that Maria Galleti, an avid collector, gave me in 2011 when she was deaccessioning favorites from her nursery are down to a mere few. There was a time when they happily multiplied in various containers on The Ledge. But I took those beauties for granted and eventually the encrusted rosettes succumbed to the humidity of urban summers because I stopped paying attention. From overly zealous watering, I lost the very hardy Opuntia fragilis grown by another rooftop gardener. It is a spiny miniature prickly pear cactus that “even the pigeons don’t pick apart,” said Michael who had been growing this little number “in the same pot 365 days a year and never watered it.” Coming out of winter, I helplessly watched a spiky rosette of Yucca nana die after I had forgotten to turn the pot on its side, and the crown rotted.

Plants come and go in our lives, and as Joseph Tychonievich, editor of the Quarterly emailed, “I always like it when authors mention things that went wrong or refused to thrive because it is helpful for beginning gardeners to know that killing plants now and again does not mean that they are a bad gardener. Failure is part of the gardening process as it is for any art.”

So even if I can pick a mini-harvest of fraises des bois to dribble on warm buttered English muffins or cool mango sorbet, it was a major disappointment that I could not cultivate small-scale blueberry bushes on The Ledge. Into three gorgeous Italian Della Robbia pots, with pudgy little clay fruit and berries going around the belly, I planted a troika of Vaccinium ‘Jelly Bean’ because that variety was selected for containers. The bushes displayed colored leaves in almost every season and I loved pruning their dwarf globular shapes, but perhaps it was premature to name a portion of my aluminum ledge Blueberry Hill. Ultimately, I was unsuccessful in protecting my crop from the birds. As I mentioned earlier, commercial farming is not my thing.

The Ledge is twenty inches (51 cm) deep and fifty inches (1.27 m) above the quarry tile deck. Viewing a rock garden at chest height is like peeking into the Alpine House at Wave Hill when the windows are removed, an opportunity to get up close and personal with an intimate panorama that would get lost in Capability Brown landscapes. Visitors to my garden can unexpectedly focus on encrusted silver saxifraga with delicate beaded margins reminiscent of the ancient jeweler’s art of granulation; hairy Sempervivum arachnoideum wearing woven antimacassars in the winter, or Jovibarba clusters that look like cabbage roses, while mounding colonies of tiny Orostachys and rosettes of Rosularia nuzzle up to one another with self-protective congested habits of growth.

As someone who did not want to see bare ground but had no budget, time, or desire to scrape, prime, and paint an aluminum ledge, all of my assorted containers are as tightly packed together as passengers in a subway car.

The thick-walled English terra cotta seed tray, an American carved stone match strike, a black granite mortar from China are all doing double duty on The Ledge. A pale pink terra cotta urn with handles and incised curlicues was a gift from Tony, my Italian super, when he returned from Majorca. A small squat holy water basin of weathered Cotswold stone discovered in an antique shop near Highgrove came home with me when you could still carry inexplicable cargo into the cabin of an aircraft. Matt arrived at one of my garden parties with Joe and a hypertufa trough from their Massachusetts garden, filled with the tiniest saxifraga that he and I have ever seen. Lori’s hypertufa cylinder is covered with enough moss to finally make it indistinguishable from real tufa. And then there are the multitudinous chocolate-colored terra cotta vessels that my dear friend and rock garden mentor, Larry, threw on his potter’s wheel. Provenance adds an inexplicable dimension to any garden.

Yet it is my troughery of NYC cobblestone that were carved out with twenty-first century diamond blade grinders and chipping guns (See The Rock Garden Quarterly, Vol. 63 No 4. Up in the Air Rock Gardening) that simulates a vision of plants living in cavities while answering my need for drystone walls. I wedge pieces of mica schist between remaining gaps in a reference to Czech crevice gardens. The sparkling metamorphic rock is also an ironic homage to Manhattan’s steel and concrete skyline that is built on top of solid bedrock which, fifteen thousand years ago, was nothing more than a boulder-strewn landscape of gravel and sand.

A back-to-front pitch forces rainwater (and my watering) to easily flow from The Ledge. Shims are placed under each vessel to keep them level and prevent slippage off the steep terrain. Pots are also set on top of pots as a stabilizing technique and to move the eye up, down and around because, as the renowned decorator Albert Hadley said, “It is important to create a ‘skyline’ in a room, things should be at different levels and heights.” One of my tallest containers, a Larry Thomas urn, is filled with an unnamed and early blooming dianthus. It is too cracked to move but seemingly lassoed together by thick entwining stems of Parthenocissus tricuspidata emerging from a planter down by my feet to form a backdrop. I am grateful for an unrepentant vine that climbs up and over The Ledge, snakes through my whole rockery and then clothes a characterless brick fortification with vibrant foliage equal to the height of leaf-peeping season in Vermont. The now scenic wall of Boston ivy holds my rock garden ledge together like a natural cliff face, same way the Japanese use shakkei, (borrowed scenery), to enlarge their landscape.

Gertrude Jekyll, the legendary English gardener of the early 20th century, might have written pronouncements like, “Good ironwork ought not to be invaded by climbing plants,” or “The fine piers are cruelly overgrown with ampelopsis.” But as one whose noble ancestry does not include a splendid manor house by her architect and partner, Sir Edwin Lutyens, it was a triumphant moment when I read another Gertrude edict, “In some cases, where the very plain brick piers have no stone cornices or capping of any kind, a restrained growth of climbing plants is allowable in order to cover this deficiency.”

Were it not for a ledge that was crying out for help, I never would have considered planting a “rockery.” Nor other rockeries for clients who come to me with pie-in-the-sky garden ideas but are about to discover that alpine plantings can lead to the genius loci – the spirit of a setting – however humble.