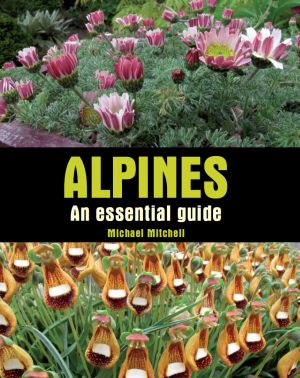

Alpines: An Essential Guide, Michael Mitchell, The Crowood Press, Wiltshire, UK (Jan. 1, 2012); 144 pp, 217 color photos, hardcover; publisher's price: £19.95; Amazon price: $40.71.

The heyday of the rock gardens was undeniably the Edwardian Era, roughly 100 years ago, especially the decade prior to the First World War. At that time, rock gardening was not a hobby pursued by a few enthusiasts, but something everyone pursued as a matter of course. Handbooks and primers were essential for the millions of gardeners in England, America and other English-speaking nations who were busy erecting rockeries right, left and center.

William Robinson produced one of the first encyclopaedic compendia of alpine plants for cultivation in the mid-Victorian Era, but we can blame Reginald Farrer for unleashing a veritable flood of imitations in the Edwardian era. I have a substantial bookcase mostly filled with surprisingly similar volumes, often rather slim, usually bound in black or dark blue or occasionally a dark, forest green. They contain almost the same disquisitions in the same order: the paean to the Alps, the pep talk on how to adapt alpines to the home setting, with many very similar line drawings of rock outcrops and many of the same plants reappearing with comforting predictability from book to book, like the same suite of actors in a soap opera over the decades: Androsace sarmentosa, Dianthus alpinus, Gentiana acaulis, Saxifraga paniculata—all the stalwarts, as bold and predictable as Humphrey Bogart, Katherine Hepburn, Cary Grant and Olivia DeHavilland. As a tribute to alpines, those same species are hanging in there (although their names are sometimes changed: Androsace sarmentosa morphs into Androsace primuloides, and now one finds gardeners “in the know” calling it Androsace studiosorum…so the dutiful among us must go out and change our labels!). Come to think of it, Olivia DeHavilland is still alive and kicking, although born in 1916.

Each decade has subsequently generated a fresh crop of rock garden primers, handbooks and guides. They have maintained the same tried and true approach as their somewhat stuffier Edwardian progenitors: generous front matter with lots of chatty suggestions as to how to place an amorphous and often strange rock garden construction in the constraints of a suburban setting. Troughs gradually made a tentative appearance in the 1930’s, becoming more and more important over the decades, as has the alpine house in British rock garden books. Color photographs jazzed things up considerably in the 1950’s, although the American classics of the genre, H. Lincoln Foster and Walter Kolaga’s tomes that came out almost simultaneously in the 1960’s were still in black and white—and still two of the very best. Since then Wilhelm Schacht’sRock Gardens and their Plants weighed in from Germany (in an edition edited with a foreword by Jim Archibald). This last is possibly my very favorite.

All this is preamble to herald Alpines: An essential Guide by Michael Mitchell. This is not a book that has been produced in a vacuum: but it is the latest and a very worthy successor to that tradition that stretches back a century and a half now. I have enjoyed pulling out some of my dusty old volumes to compare: we have come a long way indeed in the interim! Mitchell’s text is compelling and colloquial. This is not a journalist who dabbles a bit in alpines repeating what he has read, but a man who has dedicated his whole life to this passion, and has condensed decades of hard work, experience and real passion into the classic chapters guiding the beginner. Mitchell begins by telling the story of his training and starting a nursery next to his parent’s home in a rainy district of Yorkshire as a 21 year old.

His suggestions on how to go about preparing beds, creating gardens, and developing an alpine house are based on things he has done many times: you can hear his patient voice and sensible suggestions about soil, slope, drainage and siting again and again.

And he covers the gamut of issues a beginning gardener would face. I was especially pleased that he dwelt at length on garden pests including birds, slugs—of course—and many insects and diseases which invariably affect a maturing garden: most rock garden books gloss over these. The chapters on propagation from seed, cuttings and even layering are practical and especially helpful from someone who has done this a great deal over the decades.

Crevice gardening and Green Roofs make a timely appearance, although I think the former might have been illustrated with a few more photographs and some clearer exposition: this has been one of the most momentous innovations in rock garden art since its inception, and has been demonstrated to grow many challenging plants far better. There is a recipe and brief discussion of using hypertufa to create rocks for planting, but he only speaks of using cement for making “reconstituted stone”—concrete planters are surely very durable, but practically all serious rock gardeners eventually find a formula for hypertufa that works better for them, and is definitely lighter. Many beginning gardeners will find the extensive table of flowering times included as a sort of Appendix to be a useful tool in achieving a rock garden that blooms well in the summer and autumn months instead of just the spectacular show of spring.

The inevitable Plant Encyclopaedia comprises 50 pages of the book, a little more than a third of the total. This section is beautifully laid out, with wonderful color pictures on each page…and most of the classic actors make an appearance. As one would expect of a seasoned nurseryman, many of the bullet-proof classics are represented: Dianthus alpinus, Dryas octopetala, Gentiana verna, Lewisia cotyledon, and Primula auricula in several selections. A certain humid bias is revealed when Leucogenes grandicepsappears rather than much more adaptable and universal Raoulia australis. As a Coloradoan, I was flattered to see Aster coloradoensis bump the classic Aster alpinus(which also grows in Colorado, incidentally) not to mention a wealth of other late summer classics in that genus. I, for one, can’t imagine a rock garden without Aster ericoides ‘Snow Flurry’ nowadays to produce its blinding, cascading white miniature blizzard in the autumnal rock garden. The only buttercup chosen is the white Ranunculus alpestris (not an easy plant for beginners in America at least). The only Potentilla is the pink alpine P. nitida—it is magnificent it’s true, although I’ve never seen one smothered in flowers in a garden anywhere. The endangeredTrillium pusillum var. pusillum is perhaps an odd choice for that important genus…why not the commoner T. nivale, T. rivale, or T. hibbersonii instead? I blush, for these are really trivial quibbles.

I was struck to see Delosperma ‘Graaf-Reinet’ included, which I presume to be the plant sold in the United States as Delosperma ‘Ouberg’ (or some awful misspelling of the latter). I introduced this delightful miniature from cliffs on a farm near Graaf Reinet comprising that namesake mountain in 1997 on an expedition I took to South Africa with Jim Archibald. It blooms spring to fall in my home rock garden where it seems to thrive in any sunny spot—a very recent introduction that Michael perspicaciously has included into the canon. To clarify, it does not grow in the Drakensberg, but on one of the innumerable ridges and ranges that comprise the East Cape highlands—perhaps containing one of the greatest reservoirs of novel plants for rock gardens not yet introduced to horticulture. The much showier brilliant vermilion and orangeDelosperma dyeri and shocking bicolored red and purple D. ‘Firespinner’ have subsequently gotten wide billing in America, both coming from other East Cape mountains: I suspect these may take top billing in similar handbooks published in the future!

To somehow telescope the thousands of spectacular alpines now available to rock gardeners in Britain or North America into a mere fifty pages is thankless at best. Future editions should include an Arabis, Lychnis, Saponaria and especially Eriogonum—any one of which has far more classic garden plants widely available to gardeners and garden centers nowadays than Ewartia orChrysoplenium. which are still pretty esoteric fare. I grudgingly forgive Mitchell’s omission of cacti, but coming as he does from Yorkshire, where, prithee, are the wealth of miniature rock ferns that festoon the walls and rock gardens of merry England? And not a single orchid? These are now being reliably propagated from seed, tissue culture and division:Dactylorhiza at least is pretty universal in European gardens, and making inroads in America.

It is easy to quibble—this is, of course, basically a primer or beginner’s guide and cannot begin to be comprehensive. Any fifty page compendium by any rock gardener will be selective and highly personal, eliminating throngs of worthy plants and hobby horses.

I have personally found the internet has made my library of rock garden books all the more essential. The world wide web contains a plethora of links and threads and websites: there are no end of pictures and prescriptions and information. However, try clicking on a URL that goes back more than a few years and I can almost guarantee that you will not find it, or the web page has been altered. The Web is little more than a snapshot of the present. It is evanescent and impermanent…not quite like writing on water. Perhaps more like scribbling on beach sand.

A book like Michael Mitchell’s not only comprises an anthology of a keen nurseryman’s life work, it is a concrete, permanent record of our art as practiced in this decade that can stand alongside any of its predecessors, forming together an ever rising literary monument to the art of the rock garden. I’ve been pleased to have it on my bedstand and recommend that you add it to yours.

Panayoti Kelaidis has served twice as president of the Rocky Mountain chapter of NARGS, and twice on NARGS board of directors. He maintains extensive rock gardens at his home, and has collected seed for alpines on 5 continents.