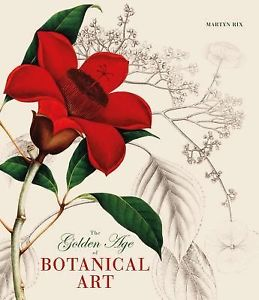

The Golden Age of Botanical Art is beautifully produced, printed, and full of spectacular color illustrations. Martyn Rix, the editor of Curtis’s Botanical Magazine for the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew, is quite adept at writing erudite and well-researched books on many aspects of botany and horticulture. Mr. Rix gives this historic publication its due in terms of longevity (225 years) and the employment of talented artists. The plates in Curtis were still being hand-colored until 1948, far longer than similar publications had turned to chromolithography.

This book promotes the sheer talent of the artists. The author investigates and discusses some of the collaborations that led to the development of botanical art. He takes one large historical step backward, prior to the appearance of botanical illustrations in herbals as tools of medicine and other sciences in the 15th and 16th centuries, to a time when artists created depictions of nature as pure aesthetic decoration on murals, tapestries, pottery, and paintings. This historical investigation provides insight into the motivations involved, beyond the quest for better scientific understandings in medicine and health.

Most of the art displayed in the book is by the important artists and scientists who worked in the 17th through 19th centuries. Their names may be familiar, but we may not thoroughly consider the collaboration of talents that evolved through Ehret, Trew and Linnaeus, and how these artists developed under different sponsors, a variety of artistic media and printing techniques, and the increasing diversity of plant material that came streaming in from all corners of the earth. Mr. Rix is very thorough in discussing these botanical offerings and the importance that was given (or not) through governing powers and independent exploration. Empress Joséphine might be an example of the perfect patron. Although Pierre-Joseph Redouté was a commercial success on his own, he enjoyed the liberty of developing artistic and printing techniques, such as stipple engraving, while under her sponsorship and portraying her garden and her collections of plants for an extended period of time. European sponsors were extremely important to most of these artists, as was the power of the British colonies in India, Africa, and the Middle East. Such international policies had everything to do with exploration in China, Japan, and most of Asia.

What is amazing, in retrospect, is the fact that this great emphasis on scientific exploration and illustration of the natural world seemed to explode in a relatively short time, as if they had an Internet through which to communicate and collaborate! We might forget the long and slow process that is still underway. Books of botanical illustration gained popularity and sponsors, some were serialized and published over sustained periods of time, and some remain in the domain of very private libraries such as The Highgrove Florilegium. Mr. Rix is quite thorough in his recognition of the diverse stylistic qualities employed by artists like Margaret Mee, who worked in nature, and the modern, but classical styles of Jessica Tcherepnine and Carol Woodin’s portrayals of the orchids of South America.

I was fortunate to have been in London for the opening of the Shirley Sherwood Gallery of Botanical Art at Kew in 1990 and it is very gratifying to know that botanical art is alive and well and we are very much a part of that Golden Age.

Michael Riley is Interim Chairperson of the Manhattan Chapter of NARGS and has been an avid gardener from the cornfields of Indiana to the rooftops of Manhattan. His fascination with botanical illustration is a simple recognition that it represents the newest discoveries and introductions of plants all over the world - who doesn't need a new plant?