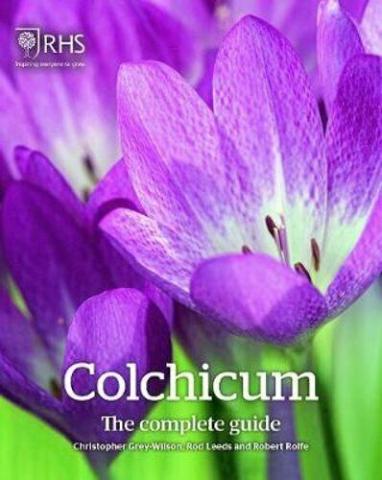

Colchicums: The Complete Guide by Christopher Grey-Wilson, Rod Leeds, and Robert Wolfe, London: Royal Horticultural Society, 2020.

Two decades ago I purchased Colchicum speciosum and C. ‘Giant’ from a bulb firm that guarantees its bulbs to be true to type. When they bloomed, they looked exactly the same to me—same height, same color, same bloom time. My insecurity as a new gardener made me think I must not be noticing some small detail, so I never complained to the company. Eventually I concluded they were both ‘Giant’.

If I had had Colchicums: The Complete Guide when those colchicums bloomed, I would have had the confidence to ask for a replacement. At the time, my only reference work was E.A. Bowles’ Crocus & Colchicum, first published in 1924. My copy was a 1985 reprint with four—count ‘em—four color photos of colchicums (but not of ‘Giant’ or C. speciosum). Autumn Bulbs by Rod Leeds (2005) had many more color photographs of colchicums, though not of every kind described. The descriptions in the book were intended for general readership and lacked measurements of flowers and leaves.

Yes, it was high time for a monograph on colchicums. The Royal Horticultural Society of Britain gathered 132 accessions of five corms each and evaluated them for three years at “an open, sunny bank adjacent to the dry garden at RHS Garden Hyde Hall.” The first job was to make sure each accession was correctly named; 40% of them were not, which gives you an idea of the job ahead of them. They addressed problems like: why doesn’t ‘Violet Queen’ look violet? Is C. giganteum a species or a cultivar? What the heck does C. bornmuelleri really look like? How do I know if this is C. byzantinum or C. cilcicum? All burning questions if you’re trying to collect colchicums and don’t want to order one you’ve already got.

I had this idea that a monograph was a pedantic, dry textbook. This book proves it doesn’t have to be. The photography is excellent and the writing is clear, concise, and as free of jargon as it can be—and still be scholarly. (There is a glossary of botanic terminology for those of us for whom infundibuliform and loculicidal are unfamiliar terms.)

And make no mistake, it is scholarly, all 576 pages of it. Species are lumped and split, taking the latest research on chromosome biology into account. There is a key for identifying species and a chart summarizing the most significant characteristics of each. There is a thorough discussion of colchicum’s cultivation history, its morphology, best cultivation practices, and the role of colchicine in human affairs. And then there is the section on cultivars, where the vast majority of garden-worthy colchicums are found. Each cultivar gets its own portrait, a general description of its history and appearance, and then a detailed description of its characteristics. If there has been any confusion about identity in the past, these problems are addressed. A bibliography and a checklist of epithets are found at the end.

For North American gardeners, there is one drawback to this book: it was written by British scientists for British gardeners. I love watching British gardening shows and reading British gardening magazines, and one thing is clear: When it comes to climate, the Brits don’t know how

good they’ve got it. Their concept of “cold winter” and “hot summer” is skewed. They have a USDA Zone 4 summer and a USDA Zone 8 or 9 winter. They don’t have the capability to evaluate the colchicums’ limits of cold hardiness—or heat tolerance.

Furthermore, colchicums behave differently in my colder climate. The authors describe leaves of some cultivars emerging right after flowering. In my climate, leaves may emerge an inch by late November, but then go into suspended animation as they are covered with snow. All colchicum leaves go into high gear as soon as the snow melts, but none truly emerge in winter. While I don’t have any experience of this myself, I have heard some gardeners in the southeast US have trouble growing colchicums.

Also, it’s unclear what other effects their more moderate climate may have had on the trials they conducted. They describe C. speciosum ‘Album’ as a prolific grower, but it grows slowly for me and is described as such by at least one American vendor. ‘Lysimachus’, the authors say, is slow to increase, but I find it multiplies much faster than ‘Album’. C x agrippinum is “one of the first to flower” for them, but I would call it a mid-season bloomer. I really don’t know to what extent these differences are due to climate. It’s possible our “race” of ‘Album’ is genetically inferior, for example.

The bottom line is, you’ll just have to do what rock gardeners always do: pay attention to the plants’ native range, and choose plants whose native climate most closely manages your own. Experiment and accept that there will be losses. If you are just dipping your toes in the colchicum waters, this may be too much book for you. But if you have grown a few varieties and want to delve deep into the genus, this is exactly the book you want.

Kathy Purdy gardens in rural upstate NY on moist, acid clay and belongs to the Adirondack chapter (which meets in the Finger Lakes region, go figure). She started growing colchicums in 1989 and now grows over 50 different kinds. Her article on colchicums is in the Fall 2021 quarterly. In addition to colchicums, she has a fondness for heirloom daffodils, intersectional peonies, and any snowdrop that will grow in her climate and doesn't cost more than she pays for colchicums.