Newfoundland is no doubt the best place in eastern North America for encountering a wide variety of arctic-alpine plants. Many of these are calciphiles restricted to the limestone barrens along the west coast of the Great Northern Peninsula. Here, the combination of exposure, climate and soil (or lack thereof) restricts the growth of typical boreal forest species such as Abies, Larix and Picea. With the lack of competition, arctic-alpines can survive. As it happens, many of our alpines have a Holarctic distribution so would be familiar to people from northern Europe. Examples include Saxifraga paniculata, Diapensia lapponica, Cornus suecica, Bartsia alpina and Silene acaulis, just to name a few. However, Newfoundland’s alpine flora has another surprise. In three widely separated regions of Newfoundland, we have outcrops of serpentine rock, a rock type rare in the world and one that is often home to endemic species or those with wide ecological tolerances. So what is serpentine rock?

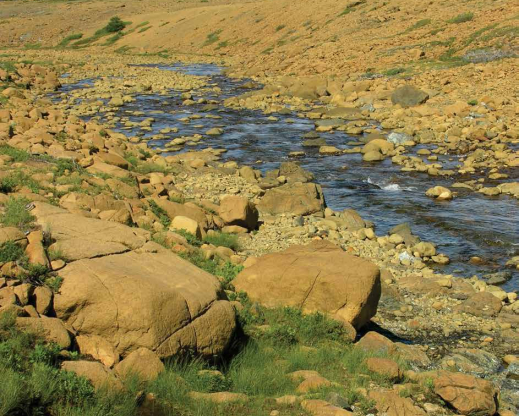

Serpentine is metamorphosed peridotite. Peridotite is the main rock that composes the oceanic crust. Only through extreme geological uplift and folding does oceanic crust become heaved above sea-level. The pressures involved in achieving this change the peridotite into the olive-green serpentinite. There are often white veins through the serpentinite, appearing like snake-skin, hence the common name. When exposed to the effects of weathering, the surface of serpentine becomes rusty-orange, the distinctive colour seen throughout our Newfoundland serpentine outcrops.

From a plant perspective, serpentine produces a host of issues for plant growth. The soils derived from serpentine are high in toxic heavy metals such as chromium, cobalt and nickel. Add to this the fact that the resulting soils are low in potassium and phosphorous and have a low ratio of calcium/magnesium. The resulting vegetation is often specially adapted to these soils. However, a few plants simply have wide ecological tolerances allowing them to survive in this hostile environment. The resulting “serpentine barrens,” at least in Newfoundland, appear devoid of plants but close inspection will reveal a surprising variety, albeit thinly distributed. There are even a few stunted shrubs and conifers that add to the haunting beauty of this landscape.

As mentioned, we have three outcrops of serpentine; the Blow-Me- Down Mountains west of Corner Brook, the Tablelands of Gros Morne National Park, and the White Hills south of St. Anthony. The only easily accessible area is the Tablelands, where a highway passes along the base of the “mountains” (really, plateaus at about 600 feet above sea level). Here, the national park has several hiking trails that will bring you into the heart of the serpentine barrens and allow access to the unique plants that grow there. The serpentine barrens of the Tablelands are just one of many reasons that Gros Morne National Park was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1987.

So what plants can you expect to see among the serpentine barrens? Well, it should first be noted that although initial appearance would suggest the area is desert-like, that is far from the truth. There are certainly dry ridges in the summer months, but the top of the Tablelands is actually covered in bogs and everyone knows that water travels downhill. This water does flow as streams in places, but more often than not, the water travels just below the surface rock layer. So while the surface looks dry, just a few inches below, the gravel (I am reticent to say “soil”!) is actually quite wet. So, the most bizarre plants seen among the serpentine rock are pitcher-plants! Sarracenia purpurea is actually our official Provincial flower, a common plant throughout Newfoundland’s copious bogs. Seeing them growing on gravel is a bit disconcerting until you realize how wet the substrate is below. Pitcher plants are not the only insectivorous plant found here; three species of sundew, Drosera, as well as butterwort, Pinguicula vulgaris, are also commonly encountered.

The plants of the pink family, Caryophyllaceae, appear to be the most serpentine-tolerant and/or adapted. Minuartia marcescens is nearly endemic to Newfoundland. It is also found on the Shickshock Mountains of the Gaspé Peninsula, Québec, which is the other serpentine region in eastern Canada. This evergreen sandwort has needle-like foliage and small white flowers throughout June and July. Similar but more tufted in appearance is M. rubella. Also similar but with broader foliage is the mat-like Arenaria humifusa. These sandworts share the serpentine barrens with other relatives in the pink family including Sagina nodosa, Cerastium terrae-novae (an endemic), Lychnis alpina and Silene acaulis.

Other species rarely encountered away from serpentine include Armeria maritima subsp. siberica, Adiantum aleuticum (an eastern North America disjunct population of this western North America species) and Artemisia campestris subsp. caudata.

The remaining herbaceous alpines found on the serpentine barrens are also found on our limestone barrens; Saxifraga aizoides, Packera paupercula, Tofieldia pusilla, Triantha glutinosa, Anemone parviflora, Primula egaliksensis, Primula mistassinica (strangely the white form is more common on serpentine than the typical lilac-pink), Erigeron hyssopifolius, Solidago uliginosa var. terrae- novae and a genetically dwarf form of Osmunda regalis. There are even a few “alpines” here that are widespread across Newfoundland including Symphyotrichum novi-belgii, Campanula rotundifolia and Sibbaldiopsis tridentata.

There are also several woody plants which call the serpentine barrens home. Two Newfoundland woodies are almost restricted to serpentine, namely Salix arctica and Rhododendron lapponicum, and the only plant more bizarre to see on serpentine than pitcher plants is Lapland rosebay. It may be rarely encountered on our limestone barrens but is far more common among the serpentine. So much for the theory that rhododendrons need acidic soil! Arctostaphylos uva-ursi is another ericaceous plant that seems at home among the serpentine. Here, too, grows a genetically dwarf form of Shepherdia canadensis. Both Juniperus horizontalis and J. communis may be encountered, with the forms of J. communis very flat and dense. Rounding out the list of woodies in this unique habitat are stunted forms of Dasiphora fruticosa, Larix laricina and Betula pumila.

The serpentine barrens of Newfoundland are like no other place on earth. While they appear lifeless at first glance, a stroll among this otherworldly landscape will reveal a host of hidden treasures.