Elizabeth Lawrence Is best known as a garden writer-- one of the best of the 20th century. Through a highly informative yet conversational style of writing, she encouraged her readers to embrace diversity in their gardens by trying something new. Even though she most often wrote of her own experiences in her two Southern gardens in North Carolina, her readers and correspondences spanned the entire county and beyond, making her a literary and horticultural icon.

Elizabeth Lawrence was born in Marietta, Georgia, in 1904. Shortly thereafter, her family moved to Hamlet, North Carolina, and then to Raleigh, so she and her younger sister, Ann, could attend St. Mary’s School, from which she graduated in 1922. Elizabeth graduated from Barnard College in New York City in 1926 with a bachelor’s degree in English with a focus on the Classics. Still curious and eager to expand her knowledge after returning home to Raleigh, she decided to earn a second degree from North Carolina State College (now University). In 1932, she became the first female graduate of the first landscape architecture program in the U.S. South, launching her career as a landscape architect. Throughout her life, Elizabeth designed and consulted on numerous gardens for private residences, commercial sites, church courtyards, and historic sites. Despite her many accomplishments as a designer, today it is her writing for which she is celebrated.

Elizabeth wrote for several popular magazines of the time: House & Garden, The American Home, and Popular Gardening, sharing her deep knowledge of plants as well as her successes and failures as she pushed boundaries in her garden.

As the frequency of Elizabeth’s publication grew, so did her confidence, and she began work on her first and best-known book, A Southern Garden: A Handbook for the Middle South (1942), which has been in print nearly continuously for the past 75 years. The first book of its kind and immediately lauded coast-to-coast, it includes Elizabeth’s plant trials and research, and specifically addresses the needs of gardeners in USDA zones 7 and 8. But more than the practical gardening information, Elizabeth’s writing style, engaging enough to appeal to gardeners and non-gardeners alike, is what made her beloved then and today.

In addition to designing, writing, and gardening, family was always a very important part of Elizabeth’s life. She never married, finding her time filled with caring for the family garden of over an acre in Raleigh; her widowed, aging mother Bessie; and their large Victorian home. As this was all becoming too much to keep up, Elizabeth made the decision that she and her mother would leave Raleigh. In 1948, Elizabeth and Bessie sold the house in Raleigh and moved to Charlotte to be close to Elizabeth’s sister Ann and her family.

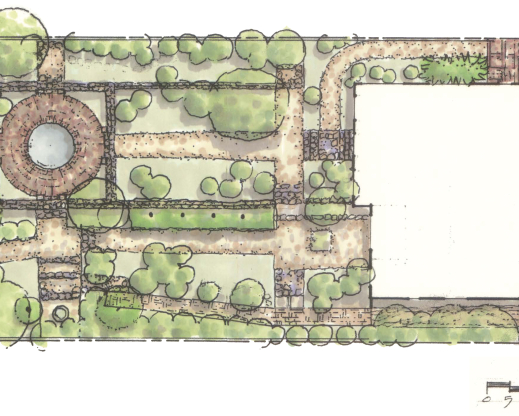

Ironically, even though Elizabeth was still a practicing landscape architect, she did not make or keep any drawings or plans of her new Charlotte garden. Thankfully there is enough historical documentation that confirms the garden design that exists today is original. The layout is formal; intersecting pathways neatly outline garden beds while subtle changes in hardscape materials create garden areas, one flowing effortlessly into the other. Elizabeth Lawrence excelled as a designer in many ways, but her keen understanding of scale and the relationship between house or structure, garden, and human, is notable. She once wrote, “Proportion is ALL,” which is especially important when it comes to a small, city lot like hers -- just 75 feet wide by 225 feet deep (about 22 m x 68 m) -- with nearly every inch cultivated.

Writing did not cease through what must have been a hectic time in settling into a new house and a new city, and neither did her endless search for new and interesting plants. I searched Elizabeth’s records for a lapse in plant orders between 1948 and 1950 and, surprisingly, I found none.

Elizabeth kept excellent records. In addition to keeping journals of when plants were in bloom, Elizabeth studied minute details of plants and noted her observations meticulously in a handwritten database of index cards. She had a scientist’s mind for documenting and accumulating research, and an artist’s sensitivity for color and combining plants.

We are incredibly fortunate to have these index cards, the metal file drawers sitting exactly where they did originally, stacked neatly on her desk in her studio, where they were (and still are) always easily accessible. About 13,000 index cards make up the collection, each card filled with information about a particular plant. Elizabeth used this information to constantly edit the garden and evaluate its plants roster. There were Southern classics like magnolias, camellias, daylilies (Hemerocallis), phlox, and an amazing collection of daffodils (Narcissus). And then there were many rare specimens and oddities, like butcher’s brooms (Ruscus aculeatus), poet’s laurel (Danae racemosa), dwarf Forsythia, and Chinese paper bush (Edgeworthia).

Friends and visitors came away with the same impression: Elizabeth’s garden was a peaceful place; it was dynamic and filled with plants. She once said to a visitor, “You have not seen my garden... you have only seen it today.”

Elizabeth cultivated many things: numerous friendships through letters, landscape design work, and popularity as a garden speaker of nearly encyclopedic knowledge. Not to mention all her writing, which earned her much more than an incredibly wide-reaching audience of enthusiastic readers. For A Southern Garden, Elizabeth Lawrence was awarded the Herbert Medal, the highest honor given by the Amaryllis Society (now the International Bulb Society). She was the first female to be awarded this honor, and one of only seven since the award’s inception in 1937. She received a citation from the American Horticultural Society for “important contributions to horticulture” and the Horticultural Writing Award from the National Council of State Garden Clubs. She was named an Honorary Life Member of the Louisiana Society for Horticultural Research and received the Award of Merit from NARGS for the eleven articles she wrote for its journal.

Perhaps her greatest joy in writing was the Sunday gardening column for The Charlotte Observer, aptly titled “Through the Garden Gate,” which ran from 1957 through 1971. Her first article, August 11, 1957, begins:

“This is the gate of my garden. I invite you to enter in; not only into my garden, but into the world of gardens – a world as old as the history of man, and as new as the latest contribution of science; a world of mystery, adventure and romance; a world of poetry and philosophy; a world of beauty; and a world of work.”

Over the 35 years in Charlotte, Elizabeth wrote manuscripts for five more books, three of which were published in her lifetime: The Little Bulbs: A Tale of Two Gardens (1957), followed by Gardens in Winter (1961), and Lob’s Wood (1971). Shortly before her death, Elizabeth handed over two manuscripts to Duke University Press. They were edited and published as Gardening for Love: The Market Bulletins (1987, ed. by Allen Lacy) and A Rock Garden in The South (1990, edited by Nancy Goodwin with Allen Lacy). In the latter, Elizabeth wrote, “But gardening is an art, and the rock garden is its purest form... All gardeners become rock gardeners if they garden long enough. The rock garden... is the most personal of all forms of horticulture.”

In declining health, Elizabeth sold her Charlotte home and garden in 1984 and moved to Maryland to be close to her niece. But before closing the garden gate, she gave plants to friends, as she wasn’t sure the next owner would be a gardener and it was important to her that those plants live on in her friends’ gardens. Elizabeth passed away on June 11, 1985.

The property was sold in 1986 and acquired by Lindie Wilson, also an accomplished gardener, who quickly realized this was a very special garden that still contained hundreds of Elizabeth’s original plants. Lindie immediately set about uncovering and rejuvenating the garden. For the next 23 years, Lindie studied and researched, and carefully dug in the dirt – always with an unshakable reverence for Elizabeth. She kept her own records in much the same way that Elizabeth did, and talked to “anyone who would listen” about the significance of Elizabeth Lawrence, her work, and her garden. It is thanks to Lindie’s inspired foresight, tireless efforts, careful stewardship, and hard work that the Elizabeth Lawrence House & Garden exists today.

Feeling that it was time to begin thinking about creating her own garden and plan for the future of this property to protect it from development, Lindie sought advice from Elizabeth Lawrence enthusiasts, preservation experts, and organizations, and in the early 2000s, founded the Friends of Elizabeth Lawrence. Representatives from The Garden Conservancy, a national non-profit organization dedicated to preserving and promoting exceptional American gardens, and the Wing Haven Foundation, a local non-profit which owned one of Charlotte’s loveliest public gardens just ten houses up the street, were among those involved from the beginning.

In 2005, the Elizabeth Lawrence House & Garden was designated a local historic landmark by the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks Commission and entered into the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Gardens. The following year, the property was listed in the National Register of Historic Places. In 2008, The Garden Conservancy was granted a conservation easement for the property, after which Lindie sold it to the Wing Haven Foundation. Later that same year, the property became one of a handful of Preservation Projects of The Garden Conservancy.

Today, the Elizabeth Lawrence House & Garden is owned and operated by the Wing Haven Foundation, and is managed in partnership with The Garden Conservancy. It is open to the public as a horticultural and historic resource.

As garden curator, my job is to see the garden through Elizabeth’s eyes and interpret that for the public as honestly as possible. It is the single hardest part of my job, and perhaps the most rewarding. I am also using the garden as the living laboratory that it was for Elizabeth, although on a decidedly smaller scale. The garden is always changing, with something new in bloom nearly every day of the year. It is still true that visitors do not see Elizabeth Lawrence’s garden… they only see it that day.

In No One Gardens Alone, A Life of Elizabeth Lawrence, Emily Wilson’s biography of Elizabeth, Wilson wrote, “She was not destined to become well known for having designed other people’s gardens, but for having inspired other people’s dreams of gardens of their own.”

Please come visit and be inspired. You won’t be disappointed!