MANY PLANTS LOVE my climate in coastal Virginia but I’ve found that most plants native to the west coast of North America hate it here. They do fine in the cooler seasons when our mild temperatures and regular precipitation are not too wildly divergent from the Mediterranean climate they evolved in; but come summer, and it is all over. The west coast is dry in the summer with no rain for months on end. Virginia, on the other hand, is soggy. If it doesn’t rain for a couple of weeks people start using the word “drought.” The humidity is so high that temperatures don’t drop much at night. I’ve gotten up at 6 am to find the humidity sitting at 100% and the temperature already above 80°F (27°C). Oh, and that’s the regular summer weather patterns. Periodically, tropical storm systems sweep through and dump torrential rain just to keep things extra wet.

Surprisingly, a few Californians will survive these conditions. Against all odds, the several selections of Zauchneria (syn. Epilobium) I’ve tried have not just survived, they’ve run vigorously out of the well-drained confines of my rock garden and are now spreading a little too happily through my regular (wet) garden soil. However, our regular rain seems to confuse them, and most years I can count the number of flowers they produce on one hand. One year, after a dry spell in late summer, they bloomed a little more, but generally, they are a bust.

I was about to give up on Californians in my garden altogether when I had a realization. There is a whole group of plants native to California that might adapt to my summer-wet conditions easily: winter annuals.

Now, when I say annuals don’t imagine I’m talking about garish petunias or impatiens. There are a whole host of plants that have adapted to the summer dryness of California by germinating in the fall, growing through the winter and blooming in the spring or early summer, that are graceful, elegant, and entirely suitable for a sophisticated rock garden.

Culture

My approach to cultivating these species is pretty simple. In September or October, once temperatures begin to cool off a little, I sow the seeds. I’ve both started them indoors under lights in containers and direct sowed them in the garden with success. During the winter not much appears to happen. They just form a cluster of a few leaves that don’t do much. But I believe that underground they are developing a large root system because as soon as the weather warms up in spring they leap into extremely rapid growth. Despite the mild climate of their origins, every species I’ve tried has sailed through snowfalls and low temperatures of around 20°F (-6.7°C) without damage.

Several species are beginning to self-sow gently through the garden, which delights me. None have become a weed and they are very easy to remove if they happen to seed somewhere I don’t want them.

Nemophila

Nemophila is a genus of winter annuals primarily native to western North America that has been a delight in my garden. In my climate, all of these begin blooming in March and carry on into May.

Nemophila maculata is my favorite of the genus so far. It has larger flowers than other varieties I’ve grown with a large blue spot on the end of each petal. In bloom, it forms a dome about six inches (15 cm) tall and wide, covered with a sheet of flowers. That over-the-top profusion of flowers reminds me of the best alpine buns. This species is now self-sowing all over my garden and I’m always happy to see it wherever it pops up.

Nemophila menziesii, going by the overly cute common name of baby blue eyes, has perfect sky-blue flowers over foliage that is green or silver depending on the form. The color of the flowers is dreamy, which makes me keep growing it though it has been less vigorous and floriferous than other nemophilas I’ve tried.

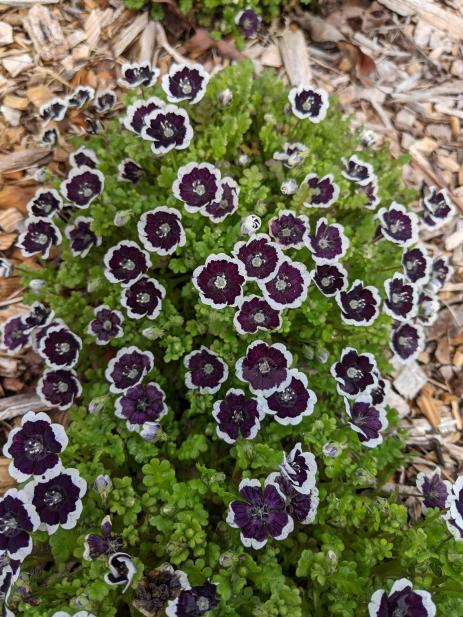

Nemophila ‘Penny Black’ is a selected form of N. menziesii, but instead of blue flowers, they are a dramatic black edged with white. This form far out-performs the blue version in my garden, rivaling N. maculata for sheer vigor and profusion of bloom. Each plant has different amounts of white on the flower, ranging from ones with a broad white margin to those that are nearly entirely black. I favor – and save seed from – the individuals with wider white margins.

Clarkia

The genus Clarkia is enormous with somewhere around 40 species. All are native to western North America, primarily California, except for the South American Clarkia tenella. There are selected forms with garish double flowers probably not suitable for most rock gardens, but most of the wild forms are elegant and beautiful. In the fall of 2020 I was looking at the seed listings from Seedhunt (a wonderful source for California native seeds and, even better, a long-time NARGS supporter) and decided to buy every species I could. I wound up with a dozen different species, many of which I am certainly going to keep growing. What follows are descriptions of my favorites of the bunch. Peak clarkia bloom in my garden is in May and June.

Clarkia tenella, the one non-Californian in the group, is also one of my favorites. The delicate plants, only four inches (10 cm) tall and wide, produce an abundance of small flowers over a very long period. It was the first species to come into bloom in my garden and is holding on after many others have finished up. Flower color is variable, but I’m growing the maroon form from Seedhunt with rich, dark red flowers.

Clarkia williamsonii is hands-down my favorite species. Though perhaps a bit tall for some rock gardens, topping out somewhere around 12-18 inches (30-45cm), the leaves and stems are extremely delicate and airy. Out of bloom, the effect is almost that of a graceful ornamental grass. Once it does start flowering those delicate stems get covered with large, richly patterned goblets that beg to be photographed daily.

Clarkia biloba has a growth habit similar to that of C. williamsonii, but instead of large goblet flowers, it produces clouds of small pink blooms. The effect of the whole plant is so airy as to be transparent, so you could easily see and enjoy other plants or rock work through it.

Clarkia breweri was the smallest of the species I grew. At first I thought it hadn’t survived the winter because the rosette of leaves was so incredibly tiny. The stems grow nearly flat to the ground, spreading just four inches (10 cm) or so before producing a dozen of the most unusual fragrant flowers I’ve ever seen, then going to seed and dying. I’ll be growing it again because the blooms are unlike any other I’ve grown, but it certainly was a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it display. The small size would certainly be suited to a trough or small rock garden, though I do wonder if the small size had more to do with my less-than-ideal conditions than the natural growth habit of the plant.

Annuals may not be typical inhabitants of the rock garden but few true alpines will grow in my climate and exploring winter annual species has opened up a whole new world of plants to enjoy. I’ve just begun experimenting with Californian winter annuals and I’m looking forward to seeing if winter annual species from other summer-dry climates like South Africa, Chile, Australia, and the Mediterranean might adapt well here also.