REGINALD FARRER WAS a unique and complex character, who many of us would probably find rather irritating. The eldest son of a landed Yorkshire family, he was born in 1880 and died in what was then called Upper Burma in 1920. In that short span, he wrote a series of unsuccessful novels, traveled widely and became a nurseryman.

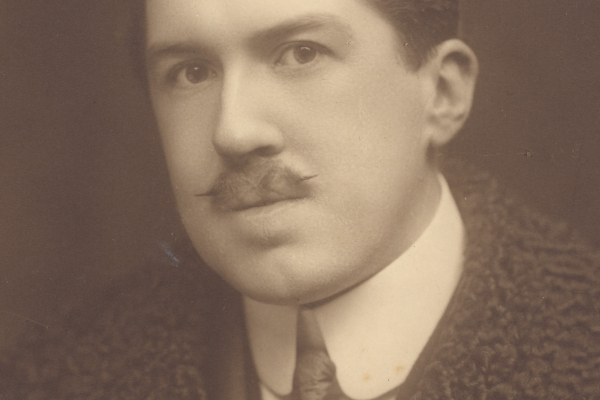

Short of stature but with a gigantic ego and a way with words, he did not suffer fools, in person or in print. His most often reproduced photograph shows a plump face, with a luxurious mustache grown to conceal a hare-lip and cleft palate (which also caused him to speak in a high-pitched squeak); the plumpness was not restricted to his face, to judge by Euan Cox’s tactful description of “a frame which was hardly built for long days of climbing and searching.” He stood for Parliament as a Liberal, but spent all his campaign funds on plants; later he experienced the Western Front as a war correspondent. Following early travels in Korea and Japan, he became a Buddhist, which went down very badly with his family, with whom his life was always one long skirmish. Nor would it have helped that he was clever, a trait regarded by many upper-class English people as deeply suspicious. And he was gay at the time when Oscar Wilde was walking the treadmill in Reading Gaol.

Above all, however, he is remembered as the founding father of rock gardening, even its patron saint, proselytizing for a natural style of rockwork and carefully prepared soils in which to grow the alpines he wrote about in glowing terms. Who could fail to chuckle at his disparaging descriptions of the rockeries then in vogue, of the “dog’s grave” and “almond pudding” varieties (though neither is wholly extinct), or lap up some of the flamboyant descriptions of his favorite plants?

The Farrer family owned – and indeed still do – the vast Ingleborough estate in North Yorkshire, which encompasses the square-topped peak of Ingleborough, a regional landmark at 2,372 feet (723 m). With its lower slopes formed of carboniferous limestone in classic karst formation, and its upper levels of the hard sandstone known as millstone grit, the mountain (as we call it) supports a wide diversity of habitats and a rich flora, including many “alpines,” which spread out over the surrounding limestone hills of the Yorkshire Dales. Primula farinosa is locally common, and Saxifraga oppositifolia still grows on the highest coldest parts. Open woodlands have nice things like Convallaria majalis and Aquilegia vulgaris as natives, but even in Farrer’s time the prime specialty of the district, Cypripedium calceolus, had been harried to almost total extinction by collectors.

It was, therefore, an ideal habitat for a plant-obsessed boy, educated at home on account of his physical disabilities (he barely spoke until he was 15, after which he hardly stopped), and he was able to make his debut in print at the age of just 14 by publishing a new location record of a rare plant (as Arenaria gothica, now Arenaria norvegica subsp. anglica, endemic to the Yorkshire Dales). About the same time he started constructing his first rock garden in the grounds of the family home, Ingleborough Hall, falling in love with the waterworn limestone as (in his view) the perfect stone for the rock garden. His avid recommendations were to lead to the despoliation of many areas of the limestone pavement he so loved, as gardeners followed his advice, including myself when constructing the rock garden at my parents’ home almost 30 years ago. In those bygone days of biological plenty, Farrer and his contemporaries had no qualms about collecting whatever they fancied from the wild, often in large quantities for both private and commercial use, in his case supplying his own Clapham Nursery.

His first rock gardening book was My Rock Garden (1907), a great success, soon followed by Alpines and Bog Plants (1908) and In a Yorkshire Garden (1909). Then there were the travel books, Among the Hills, subtitled A Book of Joy in High Places (1911) and The Dolomites (1913), enthusing himself and his readers into ecstasies over the floral delights of the Alps. By the time he wrote The Rock Garden (1912), these and a host of articles in the horticultural press had firmly established him has the rock-gardening authority and he could happily write: “As for books on the subject, I should be an idiot if I didn’t urge you specially to read my own. And there are others.”

These works were mere preliminaries to the magnum opus that is The English Rock Garden, first published in 1919, an encyclopedia of plants Farrer deemed suitable for the rock gardener to grow. Many were but names to him, ferreted out in what must have been a genuinely thorough literature search and written-up in 1913 (the man must have had prodigious energies!). In 1914 he went to the Tibetan borderlands of Gansu in western China with fellow plantsman William Purdom, having selected that area as being likely to produce plants well-suited to the English climate (a view modern plant-explorers tend to share). Their experiences, though typically written up by Farrer as if he was the only participant, were recounted in the two volumes of On the Eaves of the World (1917), covering 1914-15, and the posthumous The Rainbow Bridge (1921) for 1916: the balance has been redressed in the recent book Purdom and Farrer, Plant Hunters on the Eaves of China, by Alistair Watt (2019). As the preface to The English Rock Garden recounts, the text “was corrected for press at Lanchou-fu [now Lanzhou]… during the winter of 1914. The exigencies of war have delayed its appearance ever since…” It was only on emergence from Gansu in 1916 that they discovered the full horrors of the First World War.

In The English Rock Garden Farrer was able to give free rein to his wordy flights of fancy and plant snobbishness, with “miffs,” “mimps,” and “squinny” all being frequent terms of disapprobation. A typical example might be the entry for Gentiana andrewsii, which “is the Gentian that never wakes up. It has a slender stem of some 9 inches, at the top of which in summer appear two or three bulging bags of dull dark blue, tipped with white. These give high hope of glory; unfortunately they never do any more. In America, where it lives, the disappointing plant is known as Dumb Foxglove, and, as it never opens or has any charm, there seems no reason, except its indestructible easiness, why it should so often find a place in catalogs.” (No longer, in the UK at least, as no nurseries list it in the RHS Plant Finder for 2018.) But it’s memorable stuff and one cannot fail to enjoy a description of oenothera as “a group of plants as polymorphic as a range of clouds at sundown;” “the irresistible silver wads” of Eritrichium nanum “nestling into the highest darkest ridges of the granite” (and on for no less than six pages), or the immortal description of oncocyclus iris as “silken sad uncertain queens,” “chief mourners in their own funeral-pomps.”

The end of the war in November 1918 enabled him to leap back into action, immediately planning a trip to northern Burma (now Myanmar) in 1919 with a young man called Euan Cox, who was to keep the fire of Farrer’s memory alight with two accounts of this expedition, Farrer’s Last Journey (1926) and The Plant Introductions of Reginald Farrer (1930), illustrated by a sample of Farrer’s field sketches in watercolor. They are not the finest of botanical art, but are very charming and convey the feel of the plants in the wild.

Cox went on to establish the great rhododendron collection and nursery at Glendoick in Perthshire, Scotland, and his grandson Kenneth has recently expressed his debt to Farrer in his superb Woodland Gardening (2018). In her admirable essay on Farrer, A Rage for Rock Gardening (2002), Nicola Shulman reveals that relations between the two men were not entirely cordial for the whole time, but by 1926 Cox was able to write generously: “His character was so intricate that it is impossible… to make definite statements. All who knew him recognized his moods, and if they were wise, laid their plans accordingly. His learning was quite out of the ordinary, and I was content to sit at the feet of the master. A year is a long time to be alone with a single companion, but we came through with flying colors and with our friendship unimpaired.” Farrer himself stayed on in Burma, working at his collections through the summer monsoon of 1920, but in early October he became ill and died, apparently of diphtheria.

How should we assess Reginald Farrer’s legacy, a hundred years after the publication of The English Rock Garden and almost a century since his death? His collections of European alpine plants soon disappeared unremarked into the mixing pot of garden stock, though a few of us still grow the mossy Saxifraga ‘Wallacei’ as a direct descendant of stock bought from the Clapham Nursery: “the flowers are pure white, of enormous size and amplitude, produced in generous branching sprays that hide the whole green wave in early summer with a crest of refulgent snow.” His Gansu collections arrived in the midst of the First World War, when everyone’s attention was diverted, but of these Gentiana farreri appeared from a packet labeled “mixed muck.” Probably the most important of all his plants is the winter-flowering Viburnum farreri, though it had previously been introduced by Purdom, and another from Gansu is the lovely Buddleja alternifolia. Few plants became established from Burma, but among them are two we grow in the Yorkshire Arboretum, the early-flowering scarlet Rhododendron mallotum Farrer 815, with rich rufous indumentum, and the shimmeringly glaucous, drooping-branched spruce Farrer 1435, named Picea farreri only in 1980. His rock gardens have disappeared, and Ingleborough Hall is an outdoor education center belonging to Bradford City Council. Only in the ravine above the house, in a fault that exposes acidic rock among the limestone, are any of Farrer’s plants to be seen: towering old rhododendrons fighting with the woodland trees, a magical sight when in flower. Joseph Tychonievich and I snuck in to see them one spring; otherwise, they have to be viewed from the path leading from Clapham village to Ingleborough – for which the Farrer family grants right of access for a small fee paid through a ticket machine.

Farrer’s prolific writings assured him an unassailable place in the rock gardening literature for the first eight decades of the twentieth century: it is noteworthy that the last reprint of The English Rock Garden appeared in 1980. It was this that I was awarded as a school prize in 1985, costing £35 from the Royal Horticultural Society’s bookshop at Wisley. The prize itself was only £30-worth of books, so a fiver had to be put to it from family funds. It has been a constant companion ever since, referred to on occasion when a picturesque quote is required or other books fail to provide information. The baton has passed on through the decades, as is inevitable, though the replacement Encyclopaedia of Alpines from the Alpine Garden Society is itself now 25 years old. The Alpine Garden Society continues to award the Farrer Medal to the best plant in each of its shows, ensuring the constant evocation of his name in rock gardening circles.

A perusal of The English Rock Garden will take you on a roller coaster of words, conjuring up images of glowing alpines or mountain scenery. There’s no wonder generations of gardeners found it inspiring. The present-day reader may well revolt at the purple prose, be irritated at the weird spellings and pronunciation diktats insisted upon by Farrer, and think that much of the cultivation advice is utter tosh. But this does not affect The English Rock Garden’s seminal position, or diminish its revolutionary influence a hundred years ago – and there are times when one just has to wallow in its words for pure pleasure, as Farrer did.

Many thanks to the The Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh (RBGE) Archives for providing images for this article.

The RBGE Archives have looked after an incredible collection of Reginald Farrer’s letters, photographs, lantern slides and paintings since they were donated by his family in January 2005.

The Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh has a website www.rbge.org.uk, and details of the Farrer collection can be found by searching the Archives catalogue there http://atom.rbge.info/