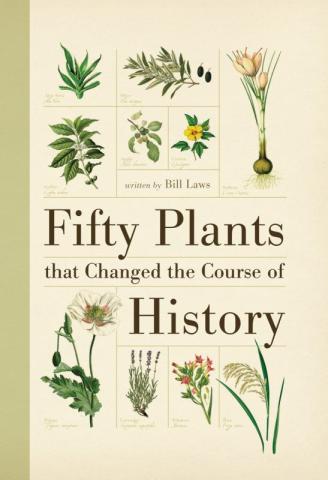

Fifty Plants that Changed the Course of History, Bill Laws, Firefly Books, Buffalo, New York (Sept. 14, 2011), 224 pages, hardcover; publisher’s price: $29.95; Amazon price: $19.77.

Is it possible that a mere 50 plants changed history? I won’t argue because this is a terrific book that will keep you on the edge of your seat. Zippy prose masks an extraordinary amount of spellbinding facts and anecdotes about these plants—among them crabapple, bamboo, and lavender—that humans enjoy for seemingly limitless purposes, most of them taken for granted. Included are some we also fear: opium poppy and coca (that’s cocaine—not to be confused with cacao, or chocolate, also included).

For example, sunflowers started their cultivated life among North American Indians, but were improved in Russia when Stalin realized their many commercial potentials (mostly for cooking, but also for life belts—its stem pith has “a lower specific gravity than cork”). Yet sunflower’s ultimate fame came from Vincent van Gogh’s golden flowers that “lifted his depression” as he sought to capture their essence in the late 1800s. A century later, the sale of one of his sunflower paintings set an art world record.

Then there is the tale of the Peruvian Indians who used the bark of a tree they called “quina quina,” the source of quinine, to treat malaria. Their discovery ultimately led to “fantastic fortunes” for some, and a history of “love, deceit, corruption, and inter-governmental conspiracy,” that could rival “any work of fiction.”

In between these fascinating yarns, a serious conservationist’s voice is unmistakable. For instance, author Bill Laws notes how “King Cotton” was not only a mainstay of the slave trade in the 18th and 19th centuries, but also led to forced migrations of Native Americans who occupied the land. And while mid-19th century America exported millions of bales per year, the growing methods were “killing the soil.” To this day, “more chemicals are sprayed on cotton than any other crop,” Laws writes. Cotton uses less than three percent of farmed land but is treated with “a quarter of the world’s pesticides.”

All the illustrations are from other works, but, honestly, I hardly looked at them because the prose packed such a wallop. This book will mesmerize plant-lovers and non-gardeners alike.

Linda Yang is author of The City Gardener’s Handbook (Storey Publishing), now in its 21st year of publication, and a former garden writer for The New York Times. She is a member of the Manhattan Chapter of NARGS.